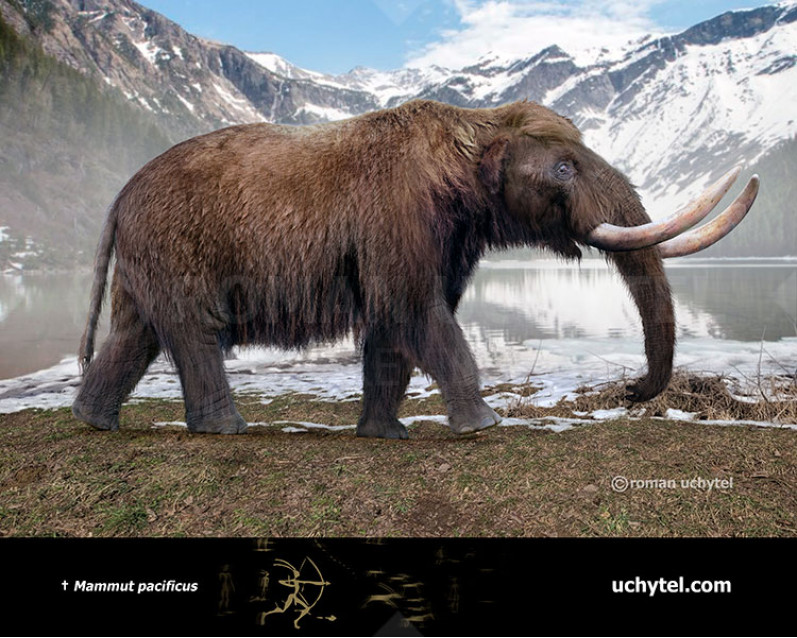

Pacific Mastodon (Mammut pacificus)

202129202129Pacific Mastodon (Mammut pacificus)

Order: Proboscidea

Family: Mammutidae

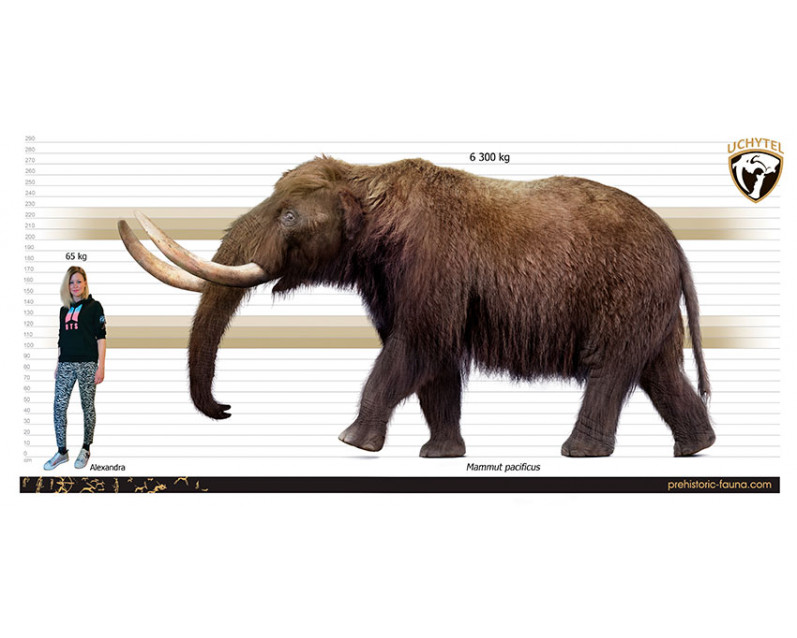

Dimensions: length - 4,5 m, height - 2.4- 2.8 m, weight - 6 300 kg

Expansion: Pleistocene of western North America.

Mammut pacificus a new species of mastodon from the Pleistocen differs from the contemporaneous M. americanum. Mastodons lived in herds and were predominantly forest-dwelling animals that fed on a mixed diet obtained by browsing and grazing with a seasonal preference for browsing, similar to living elephants.

n recent decades, our knowledge of mastodon anatomy has made strides as has our understanding of their disappearance within the context of the late Pleistocene extinction of the North American megafauna. While the genus Mammut was divided into several different species during the first half of the 20th century, these taxa have not withstood detailed scrutiny, lacking discovery of additional specimens. Therefore, even though some taxa have never been formally synonymized with M. americanum , it has been generally accepted that by the Pleistocene there was only a single, highly variable mammutid species in North America, Mammut americanum.

Mammut fossils are particularly common in the eastern US, especially in Florida, New York, the Midwestern states of Missouri, Indiana, and Illinois, and the Great Lakes region, including Ohio and Michigan; specimens from these areas have dominated studies of mastodons. While isolated remains, primarily of teeth, were discovered in California as early as the 1860s, based on specimen labels from the collections at the University of California—Berkeley Museum of Paleontology, prior to the 1990s the only significant concentration of western mastodon remains was from the asphalt deposits at Rancho La Brea in southern California, and even these were relatively rare and made up a minuscule percentage of the Rancho La Brea fauna. Based on these limited remains, Stock & Harris (1992) suggested that Rancho La Brea mastodons were smaller than their eastern counterparts, while Trayler & Dundas (2009) found that Rancho La Brea mastodon molars, specifically m3s, were narrower than those from Missouri, although both of these studies considered the Rancho La Brea samples to be referable to M. americanum.

The Diamond Valley Lake fossil collection is housed at the Western Science Center (WSC) in Hemet, CA, USA, and a portion of that collection forms the majority of the WSC public exhibits. One of the most prominent individual exhibit specimens is a partial mastodon skeleton (popularly known as “Max”), which was reported by Springer et al. (2009, 2010) as the largest mastodon known from the western US. In 2014, while preparing updated information panels for the exhibits, it was recognized that Max had small, narrow third molars despite the large size of other skeletal elements. As we accumulated data and began to observe consistent (if partially overlapping) quantifiable differences in character distributions between eastern and western mastodons, we found that the simplest and most robust explanation for these differences is that we were observing two morphologically distinct lineages, justifying separate species designations for the two populations.

Pacific Mastodon (Mammut pacificus)

Order: Proboscidea

Family: Mammutidae

Dimensions: length - 4,5 m, height - 2.4- 2.8 m, weight - 6 300 kg

Expansion: Pleistocene of western North America.

Mammut pacificus a new species of mastodon from the Pleistocen differs from the contemporaneous M. americanum. Mastodons lived in herds and were predominantly forest-dwelling animals that fed on a mixed diet obtained by browsing and grazing with a seasonal preference for browsing, similar to living elephants.

n recent decades, our knowledge of mastodon anatomy has made strides as has our understanding of their disappearance within the context of the late Pleistocene extinction of the North American megafauna. While the genus Mammut was divided into several different species during the first half of the 20th century, these taxa have not withstood detailed scrutiny, lacking discovery of additional specimens. Therefore, even though some taxa have never been formally synonymized with M. americanum , it has been generally accepted that by the Pleistocene there was only a single, highly variable mammutid species in North America, Mammut americanum.

Mammut fossils are particularly common in the eastern US, especially in Florida, New York, the Midwestern states of Missouri, Indiana, and Illinois, and the Great Lakes region, including Ohio and Michigan; specimens from these areas have dominated studies of mastodons. While isolated remains, primarily of teeth, were discovered in California as early as the 1860s, based on specimen labels from the collections at the University of California—Berkeley Museum of Paleontology, prior to the 1990s the only significant concentration of western mastodon remains was from the asphalt deposits at Rancho La Brea in southern California, and even these were relatively rare and made up a minuscule percentage of the Rancho La Brea fauna. Based on these limited remains, Stock & Harris (1992) suggested that Rancho La Brea mastodons were smaller than their eastern counterparts, while Trayler & Dundas (2009) found that Rancho La Brea mastodon molars, specifically m3s, were narrower than those from Missouri, although both of these studies considered the Rancho La Brea samples to be referable to M. americanum.

The Diamond Valley Lake fossil collection is housed at the Western Science Center (WSC) in Hemet, CA, USA, and a portion of that collection forms the majority of the WSC public exhibits. One of the most prominent individual exhibit specimens is a partial mastodon skeleton (popularly known as “Max”), which was reported by Springer et al. (2009, 2010) as the largest mastodon known from the western US. In 2014, while preparing updated information panels for the exhibits, it was recognized that Max had small, narrow third molars despite the large size of other skeletal elements. As we accumulated data and began to observe consistent (if partially overlapping) quantifiable differences in character distributions between eastern and western mastodons, we found that the simplest and most robust explanation for these differences is that we were observing two morphologically distinct lineages, justifying separate species designations for the two populations.

-797x638.jpg)

-70x56.jpg)

-346x277.jpg)

-346x277.jpg)

-2015-346x277.jpg)

-346x277.jpg)